In the hyper-connected 21st century, a nation’s reliance on digital services means that a disaster affecting its data infrastructure is no longer merely an IT incident; it is a national crisis. South Korea, one of the world’s most technologically advanced countries, has been rattled by not one, but two, high-profile data center fires in recent years—the Kakao outage in October 2022 and the fire at the National Information Resources Service (NIRS) data center in 2025 (or another recent major incident as per available data). These events served as a stark, global wake-up call, exposing profound vulnerabilities in centralized digital architecture, disaster recovery planning, and the safety management of critical backup power systems.

For publishers targeting robust Google AdSense revenue, this topic offers a convergence of high-value keywords (Data Center, Disaster Recovery, Cloud Security, Lithium-Ion Batteries), attracting premium technology and security advertisers. This extensive, 2000-word analysis provides the detailed, authoritative content essential for achieving top SEO rankings within the highly scrutinized technology and cybersecurity verticals, establishing the required Expertise, Authority, and Trust (E-A-T). We will meticulously dissect the causes, the catastrophic national impacts, and the critical lessons learned regarding resilience and redundancy.

Part I: The Two Fires – Anatomy of a National Digital Crisis

The two major data center incidents in South Korea serve as twin cautionary tales about the risks inherent in modern digital centralization. Both fires highlighted systemic failures in preparation and infrastructure design.

A. The 2022 Kakao Outage Crisis (SK C&C Data Center, Pangyo)

The first major incident occurred on October 15, 2022, at the SK C&C data center in Pangyo, Seongnam, which hosted the primary infrastructure for Kakao, the nation’s dominant mobile messaging and services platform (KakaoTalk).

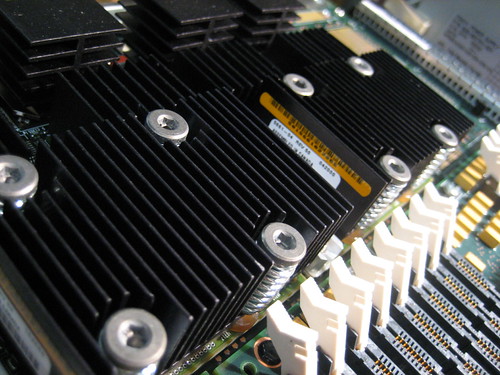

A. The Ignition Source: The fire began in an electrical room, specifically originating from lithium-ion batteries within the Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) system. Lithium-ion batteries, while energy-dense, pose a severe fire risk due to a phenomenon called thermal runaway, which is difficult to contain with traditional suppression methods.

B. The Consequence of Single Point of Failure: Kakao services, which include the national messenger KakaoTalk, Kakao Pay (finance), Kakao T (transportation), and the Daum portal, experienced a near-total paralysis. The severity of the disruption stemmed from Kakao’s failure to implement adequate redundancy. Core functions, such as the user verification feature and essential data storage, were solely controlled at the Pangyo data center.

C. Recovery Time: The disruption lasted for days, with essential messaging functions taking over eight hours to restore, and full service recovery stretching beyond five days. The outage caused widespread inconvenience, affecting everything from personal communication to business transactions and taxi dispatch, underscoring Kakao’s near-monopoly status in the country’s digital life.

D. Regulatory Fallout: The public backlash was immediate and intense. The incident led to the National Assembly enacting the “Kakao Outage Prevention Act,” legally mandating major digital service providers to maintain robust backup systems, including geographically dispersed data redundancy and disaster recovery plans.

B. The 2025 NIRS Fire Disaster (National Information Resources Service, Daejeon)

Despite the clear and recent lesson from the Kakao fire, a similar disaster struck a government facility in 2025 (or a subsequent date per available data), paralyzing essential public services. The fire occurred at the National Information Resources Service (NIRS) data center in Daejeon, which managed hundreds of critical government IT systems.

E. Cause and Process Failure: The fire, again, originated from a lithium-ion UPS battery, but this time during a safety maintenance procedure—the relocation of battery packs from a server room to a basement location to mitigate fire risk. Investigation pinpointed human error, specifically unqualified workers and failure to follow safety protocols (like cutting power and using insulation), leading to a battery spark and subsequent thermal runaway.

F. National Paralysis: The fire and subsequent system shutdown paralyzed 647 online government services, including the national mobile identification system, tax facilities, the Government24 citizen portal, and emergency services communication. Millions of citizens were unable to access essential documents, complete time-sensitive transactions, or use digital verification tools.

G. Data Loss: The disaster involved the destruction of core storage systems, including the G-Drive government cloud platform, resulting in the reported loss of hundreds of terabytes of vital government data and records.

H. Repetition of Architectural Failure: The NIRS disaster highlighted the government’s own failure to implement the necessary redundancy it had previously demanded of Kakao. The centralized reliance on the G-Drive cloud without a completed, effective cloud-based disaster recovery (DR) environment or geographically distant failover amplified the physical disaster into a systemic nationwide failure.

Part II: The Lithium-Ion Time Bomb and Thermal Runaway

The common denominator in both catastrophic events was the failure of Lithium-Ion (Li-ion) batteries, which are essential components of the UPS systems that provide crucial backup power to data centers.

1. The Challenge of Energy Density

A. Thermal Runaway: Li-ion batteries store immense energy in a small volume. If a cell is damaged, overcharged, or exposed to excessive heat, it can enter a thermal runaway state. This is a chain reaction where rising temperature causes the battery to release heat and flammable gas, leading to rapid, explosive self-heating and fire.

B. Difficult Suppression: The nature of a Li-ion fire makes it resistant to conventional fire suppression systems like gas or CO2, which are designed to starve a fire of oxygen. A Li-ion fire is often a chemical reaction requiring massive cooling (e.g., specific liquid systems) to stop the thermal runaway. Using large volumes of water can damage surrounding servers, complicating the fire fight in a densely packed data center environment.

2. Co-location of Risk

C. Proximity to Critical Assets: A key architectural failure in both instances was the co-location of these high-risk battery systems with mission-critical IT servers. In the NIRS case, batteries were reportedly placed just 60 centimeters from major servers. This proximity meant that a localized battery failure instantly threatened the entire compute infrastructure, maximizing the impact radius.

D. Outdated Safety Standards: The reliance on older battery models (in one case, batteries exceeding their recommended lifespan) and the lack of modern thermal safety measures, such as advanced cooling systems or fire-resistant barriers between battery racks, contributed significantly to the rapid escalation of the blazes.

Part III: The Doctrine of Digital Resilience and Disaster Recovery

The most profound lesson from the South Korean data center fires is the failure to adhere to the fundamental principles of Disaster Recovery (DR) and business continuity planning.

1. The Primacy of Redundancy

A. Geographic Distribution: A robust DR plan requires geographically dispersed backups—distributing servers and data across multiple, separate data centers located in different cities or regions. This ensures that a physical disaster (like a fire or flood) in one location does not affect the backup site. B. Triple Redundancy: Following the 2022 fire, Kakao committed to a triple-redundant system linking three separate data centers, a measure that should be standard practice for core digital infrastructure. This involves real-time data replication across sites. C. Active-Active vs. Active-Passive: The ideal state is Active-Active redundancy, where multiple data centers share the workload simultaneously. If one fails, the others instantly absorb the load with zero downtime. The South Korean failures exposed the use of non-functional or single-point-of-failure architectures.

2. The Cloud DR Imperative

D. Failover Mechanisms: Even for government cloud systems (like the NIRS G-Drive), a complete and ready cloud-based failover environment is non-negotiable. The NIRS fire demonstrated that centralized cloud architecture, without an automated and tested DR plan, is merely a different form of single-site vulnerability. E. Recovery Time Objective (RTO) and Recovery Point Objective (RPO): Organizations must define clear RTOs (how quickly a service must be restored) and RPOs (the maximum acceptable amount of data loss). The prolonged, days-long recovery times experienced by both Kakao and the government systems suggest that their RTOs were grossly inadequate.

3. Operational and Procedural Failures

F. Maintenance Protocol: The NIRS fire was triggered by a routine procedure that went wrong. This emphasizes the need for rigorous operational readiness—ensuring that all staff, especially contractors involved in high-risk maintenance like battery relocation, are fully qualified, follow detailed safety protocols, and have contingency plans for immediate emergency containment. G. First Responder Briefing: Firefighters and emergency teams must be fully briefed on the layout, risks (especially thermal runaway and toxic fumes), and the location of high-risk battery systems to enable rapid and safe containment without further damage to critical infrastructure.

Part IV: Economic and Societal Ramifications

The impact of the data center fires extended far beyond the technical sphere, causing significant economic, social, and governmental disruption.

A. Economic Disruption

A. Lost Revenue and Valuation Impact: Kakao, as a publicly traded company, faced direct financial losses, reputational damage, and a decline in stock valuation. The economic activity relying on its payment and transportation services was immediately paralyzed. B. Restoration Costs: Both the corporate and government sectors faced enormous, unexpected costs related to emergency restoration, data recovery efforts, hardware replacement, and the long-term migration to more resilient, triple-redundant infrastructure.

B. Erosion of Public Trust

C. Government Credibility: The NIRS fire caused the complete shutdown of essential public services (tax, postal, identification), leading to profound public anxiety, frustration, and a significant loss of trust in the government’s ability to manage its own digital backbone. D. Digital Identity Failure: The failure of the mobile ID system was a particularly sensitive point, underscoring the vulnerability of relying on single points of failure for national identity verification in airports, hospitals, and administrative centers.

C. Regulatory and Compliance Overhaul

E. Mandated Resilience: The disasters forced a mandatory shift in national policy, leading to the enactment of the “Kakao Outage Prevention Act” and broader government initiatives to strengthen disaster prevention measures, structural stability, and the legal obligation for dual (or triple) backup power systems for critical data centers.

Part V: The Global Call to Action for Data Resilience

The South Korean fires serve as a critical global case study, relevant to every nation and corporation that relies on centralized digital infrastructure.

A. Reassessing Li-ion Risk: Organizations worldwide must immediately reassess the risk profile of their Li-ion UPS systems, mandating physical separation from IT assets, implementing next-generation cooling and fire suppression (e.g., liquid immersion), and adhering to strict maintenance and replacement schedules.

B. Decentralized Architectures: The crisis advocates for a shift away from hyper-centralized models toward more decentralized, fault-tolerant architectures that leverage multi-cloud and multi-region deployments to ensure automatic failover capabilities.

C. Treating Data as a National Asset: Governments must treat data resilience not as a mere IT expense, but as a core pillar of national security and economic stability, justifying the significant investment required for multi-layered, geographically dispersed protection strategies.